Fashion is Inherently Political: What Americans Can Learn From The Boldly Dressed “Sapeurs” in The Congo

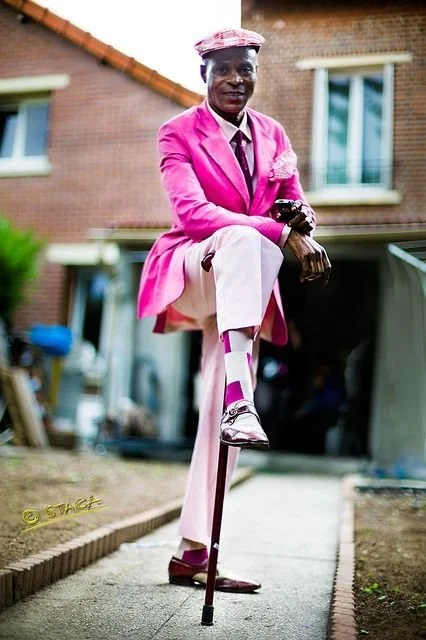

In an era of quiet luxury, minimalism, and America’s deep and infuriating obsession with athleisure, I practically started drooling upon sight of Tariq Zaidi’s photography. His work depicts men dressed in audaciously patterned three piece suits; every detail exquisitely chosen from the tie pins and the hats, to the canes and the pipes.

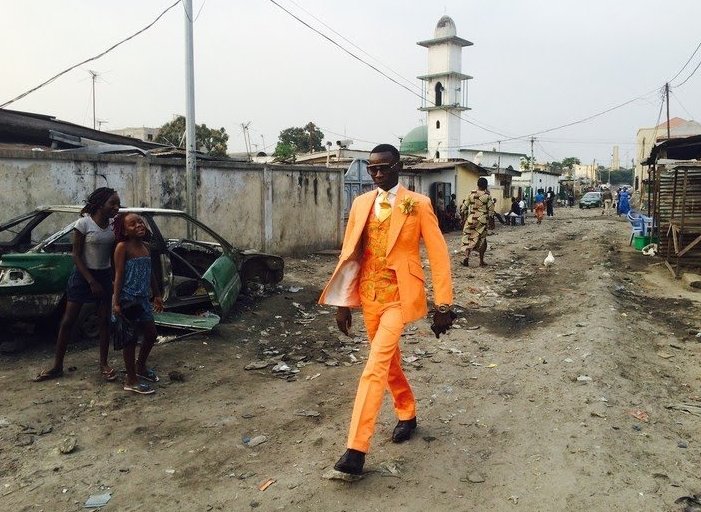

These men are part of a longstanding fashion movement concentrated in the Democratic Republic of the Congo called La Sape. SAPE stands for Société des Ambianceurs et des Personnes Élégantes (Society of Ambiance-Makers and Elegant People). These “Sapeurs” pride themselves on collecting and maintaining closets of Alexander McQueen, Yohji Yamamoto, and Pierre Cardin with a particular emphasis on Parisian designers. Their colorful crocodile loafers, however, stand in stark contrast to their settings with which they are photographed.

Aude Osnowycz in her photo series The New Sapeurs writes. "This series aims to highlight the role that Sapeurs play in their struggle against their predicament… while they dress rich, they live in one of the poorest countries in the world.”

This eccentric dressing can be traced all the way back to the turn of the 20th century with the colonization of the Congo by the French. What started as a means of cultural assimilation in the early half of the century turned into a peaceful yet lively protest against an oppressive dictatorship that dominated the country in the later half.

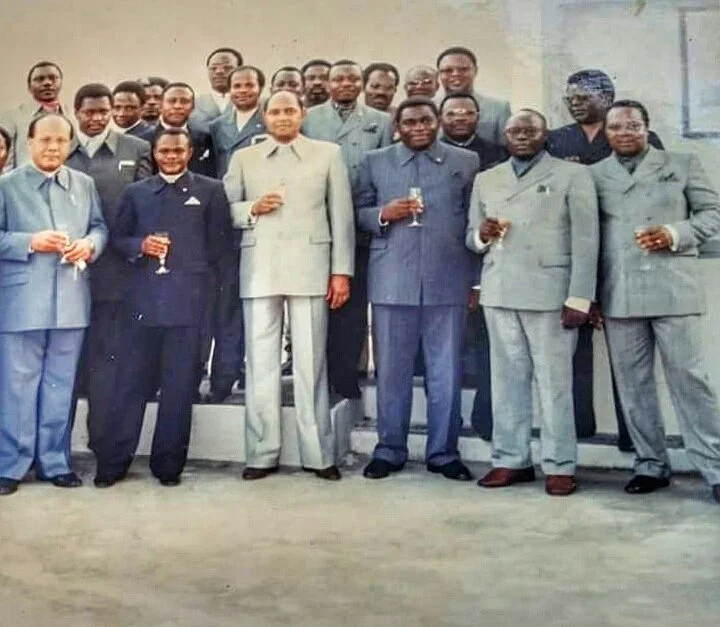

Mobutu Sese Seko rose to power in the 70s by way of a coup and execution of his democratically elected predecessors. Motubu greatly inhibited civil liberties during his reign; including restrictions on dress. The abacost, a plain pant suit, became the national dress. Although at first merely discouraged by the regime, La Sape and western style dress was eventually outright banned from 1972 to 1990.

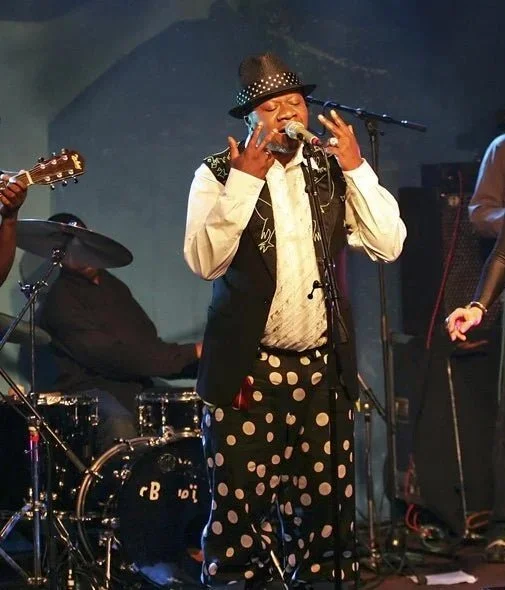

Papa Wemba, a Congolese singer dubbed the “King of Rumba Rock” emerged as a de facto leader of La Sape during this time. He, along with his music group Viva La Musica, donned La Sape on stage during their performances. This emboldened sapeurs to continue participating in La Sape and protest the dictatorship and restrictive abacost.

Sapeurs may display a face of wealth and aristocracy but most are planted deep in the working class as gardeners, carpenters, and taxi drivers. They are picking up extra shifts and probably cutting corners in other parts of their life to support their love of Sape.

Tanvi Misra (BBC) reports, “One sapeur “[Hassan Salvador] earns $1,000 a month working as a warehouse manager, and about 20% of that goes on clothes. Feron Ngouabi spends all of his earnings as a fireman on clothes… Fortunately he owns two taxis, which bring in extra cash.”

Stephanie McCrummen writes for the Herald Tribune, “There are wealthy sapeurs -- singers with money and diamond dealers -- and many have girlfriends who bemoan their spending habits. But most are like this group, who at the end of their strutting borrowed money for bus rides to their homes across Kinshasa, a capital so neglected it appears to have been bombed and left to decay, its ruins smothered in weeds.”

What they lack in financial capital, they greatly make up for in social capital.

McCrummen recounts children recognizing local Sape celebrity Kindingo or “Mzee”, pointing him out and cheering him on along his walk home. However, once inside she learns a very different side of Mzee. “He has no job prospects. His father earns a pension of $20 a month. ‘Life is difficult,’ Kindingo said. "Life is bad. Eating is a problem. But when you dress, people admire you.”

Mona M. Ali, a reporter covering the Sapeurs, writes “Being a sapeur is about clothes, but it’s also about an attitude and a way of being in the world. It’s telling the world that no matter what my environmental condition is, I am still human, and I still have dreams and aspirations. And I can still look amazing if I want to.”

***

Fashion is inherently political. When the Met Gala’s 2025 theme was revealed to be “Superfine: Tailoring Black Style” I think I audibly heard the global sigh of fear and anticipatory disappointment; Not in the theme itself but in the guests and their ability to execute such a nuanced, political, and inherently BLACK theme.

The theme was based around Monica L Miller’s book Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity.

Modern La Sape in the Congo is one form of Black Dandyism, however “Dandyism” is an umbrella term that also catches the class-defying dress that stretched through Victorian England, 1700s France, and post-slavery America.

The fear that prickled down my spine when I thought of non-black nepo babies gearing up to take on this theme, would have killed Anna Wintour. With such an obvious and disheartening lack of Black creative directors at the helm of major fashion houses, I was left to put my trust in… Christian Sirano and Marc Jacobs? What do you Sydney Sweeney have to share about the emergence of style as a means of rebellion and personhood for Black Americans in post slavery America? Will you support Wheat Thins in the fight against lyme disease?

When a Black person dons La Sape it is counter culture. It is challenging colonialism’s definition of class. When a white person wears it… it just is referencing colonialism.

Yinka Shonibare's series of photographs, Diary of a Victorian Dandy (1998) reimagines one day in the life of a dandy in Victorian England, through which the author challenges conventional Victorian depictions of race, class, and British identity by depicting the Black Dandy, surrounded by white servants. Fashion changes its meaning based on context: The same outfit can have different meanings depending simply on who is in it.

Rikki Byrd, a lecturer from Washington University, explains “The Black Dandy is often making a concerted effort to juxtapose himself against racist stereotyping seen in mass media and popular culture [...] For dandies, dress becomes a strategy for negotiating the complexities of Black male identity.”

I feel it's the most polite way possible to simply suggest that maybe the way things are has no basis; A social hierarchy based on race is not of sound reason. Through no words at all, Black Dandyism challenges these long standing institutions by just merely existing in aristocratic dress.

Miller describes Black Dandyism as “a strategy and a tool to rethink identity, to reimagine the self in a different context. To really push a boundary—especially during the time of enslavement, to really push a boundary on who and what counts as human, even.”

Manu Dibango, fellow rumba musician, said of Papa Wemba’s fashion philosophy, "His whole attitude about dressing well was part of the narrative that we Africans have been denied our humanity for so long. People have always had stereotypes about us, and he was saying dressing well is not just a matter of money, not just something for Westerners, but that we Africans also have elegance. It was all about defining ourselves and refusing to be stripped of our humanity."

As America falls deeper into the clutches of facism, the culture is trending more and more traditional, milkmaid dresses at the club, mass tattoo removals, makeup trends are more muted and simple. Dandyism possibly asserts itself as an answer to this troubling shift. Portraying masculine men in fancicful dress and still being thought of as powerful, and having status.

Superfine is the first menswear-focused Met Gala exhibition since 2003’s “Men In Skirts.” Men feel left behind. And I feel, in retaliation, they have closed themselves off even more. Younger generations are less likely to compromise on political beliefs and take a partner on the other end of the political compass. Men feel rejected and then jump, leap, and skip further away from human connection.

Men are finding their identity in “manhood” but exhibitions like Superfine dare us to interrogate what manliness looks like.

Superfine says men feel forgotten? Let's highlight them! Let's show them what is possible when they decide to break boundaries instead of put them up. In the Sapeurs’ case, their bright colors and ruffled fabrics gained them social capital. They became pillars of their society, someone to look up to.

I feel like these boys are waiting for someone to come along and tell them they are worth something; by a woman, by god, by their bosses, by an audience. Black Dandyism, as a foil, is about forging an identity through creation.

“Agency, autonomy, and choice are quintessential to the Black Dandy. Despite its origins being rooted in enslavement, this imposed dress code on Black men also was born out of a revolt against the dissolution of choice. Their dress was often something that was decided by their enslaver, with no consideration of how they would like to show up in the world. But, as Miller notes, through their ‘clothing, gesture, and wit’ the Black Dandy was able to traverse and name oneself. An act of creation through garments and clothes.” - Taylor Crumpton for Time